Art in Film: Skyfall, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Goodfellas and Red Dragon

Guest Feature By Eleanor Elliott-Rathbone a graphic designer with a penchant for movies whom, we at Film and Furniture, met on Twitter discussing the power of objects and furniture in film. Here she shares with us her love of art in film.

The diverse functions of the inclusion of Art works in Film – Skyfall, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Goodfellas, and Red Dragon.

In the words of French theorist Jean Mitry, ‘in any film, any image – even the least defined – is found to be loaded already with a certain meaning, even before the basic combinations come along to create eventual signification.’ What we see on screen isn’t reality, but a carefully considered depiction, crafted for the purpose of supporting the storyline and maintaining the world in which it takes place.

Painting and other works of art consistently make an appearance in film, despite the expenses a director makes to feature it. One cannot simply print out a copy of Francisco Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son in an antique frame and start rolling. The potentially catastrophic repercussions of transporting an original work of art is far too great in the minds of the galleries. Instead, a painter is often hired to replicate with precision the painting the director wishes to feature. You can read more about the lengthy process involved in featuring iconic art here >

Turner in Skyfall

Existing art, that is – art that exists outside the plot of the movie, often comes with it’s own associations. In Skyfall (2012) for example, the National Gallery, London is used as background décor for 007’s (Daniel Craig) meeting with Q (Ben Whishaw). In this scene, Turner’s most famous painting, The Fighting Temeraire is used as a catalyst for the character’s interaction with each other.

Q: It always makes me feel a little melancholy. Grand old war ship, being ignominiously hauled away to scrap… The inevitability of time, don’t you think? What do you see?

JAMES BOND: [pause] A bloody big ship.

The full title of the work is The Fighting Temeraire Tugged to Her Last Berth to be Broken Up. Q avoids the feminine personification frequently attached to ships and the like, so as to suggest parallels between The Fighting Temeraire and Bond himself.

The National Gallery website cites: ‘The 98-gun ship ‘Temeraire’ played a distinguished role in Nelson’s victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, after which she was known as the ‘Fighting Temeraire’. The ship remained in service until 1838 when she was decommissioned and towed from Sheerness to Rotherhithe to be broken up’.

The Temeraire had lived out her glory days, and once devoid of any purpose is sent away by her masters to be dismantled and destroyed, bearing much similarity to Bond and his own physical capabilities as an aging agent past his prime. The power of such a recognizable piece of art in Skyfall manages to nonverbally connote to all the film’s underlying themes in a period of 20 seconds.

The (fictitious) Van Hoytl in The Grand Budapest Hotel

Eccentric concierge Gustave (Ralph Fiennes) is the frontman of the prestigious Grand Budapest Hotel, a (fictional) ski resort in the (fictional) European Republic of Zubrowka. After the death of Madame D (Tilda Swinton) – a lover and loyal patron of Gustave, he is left an incredibly valuable painting in her will. Accused of murder by Madam D’s neglectful son Dmitri (Adrien Brody), Gustave and faithful lobby boy Zero (Tony Revolori) find themselves on the run until they can prove the concierge’s innocence.

The plot of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) hinges on the sought after and much desired painting Boy With Apple by fictional Northern Renaissance painter Johannes Van Hoytl.

GUSTAVE: [Gustave and Zero are examining Boy With Apple in Dmitri’s study] This is van Hoytl’s exquisite portrayal of a beautiful boy on the cusp of manhood. Blond, smooth skin as white as that milk, of impeccable provenance. One of the last in private hands, and unquestionably the best. It’s a masterpiece. The rest of this shit is worthless junk.

What is interesting is the differing perceptions of value each character bestows upon the painting. To Gustave, the painting is a beautiful work of art to be loved and admired, a source of entertainment, of pleasure. In Madam D’s will she writes “To my esteemed friend who comforted me in my later years and brought sunshine into the life of an old woman who thought she would never be happy again — M. Gustave H. — I bequeath, bestow, and devise, free of all taxation and with full and absolute fiduciary entitlement, the painting known as ‘Boy with Apple’ by Johannes van Hoytl the younger, which gave us both so much pleasure.” It is therefore a source of cultural capital.

Dmitri, now head of the family, values the painting because of its monetary worth yes, but also for the prosperity it exudes. The idea of a concierge owning such a painting horrifies him, and through the film we see him plotting to take it back and take Gustave down. Therefore, the painting becomes more than a painting to Dimitri – it becomes a symbol of family wealth and success.

These perceptions are hard for us, the audience to grasp. Because the painting is fictional, we are somewhat ignorant to its effects, unlike the Turner featured in Skyfall. The only character that embodies this standpoint is Zero, the refugee Lobby boy and protégé of Gustave. He, like us, is unfamiliar with the painting and its value, and in an attempt to understand it’s worth better, he inquires about it: ‘Is it very beautiful?’. Anderson doesn’t show Zero with a changed perspective once he sees and hears about the painting – If anything he seems rather unengaged compared to his mentor. Despite not presenting Zero or the audience with a clear opinion of Boy With Apple, he later inherits and keeps the artwork where it eventually resides in the ‘enchanting ruin’, The Grand Budapest. Why, we might ask? Because it serves as a reminder of Gustave and their adventures together. Not for its prevalence, not for its high culture status, but for it’s relation to him and his life. For Zero the painting holds sentimental value.

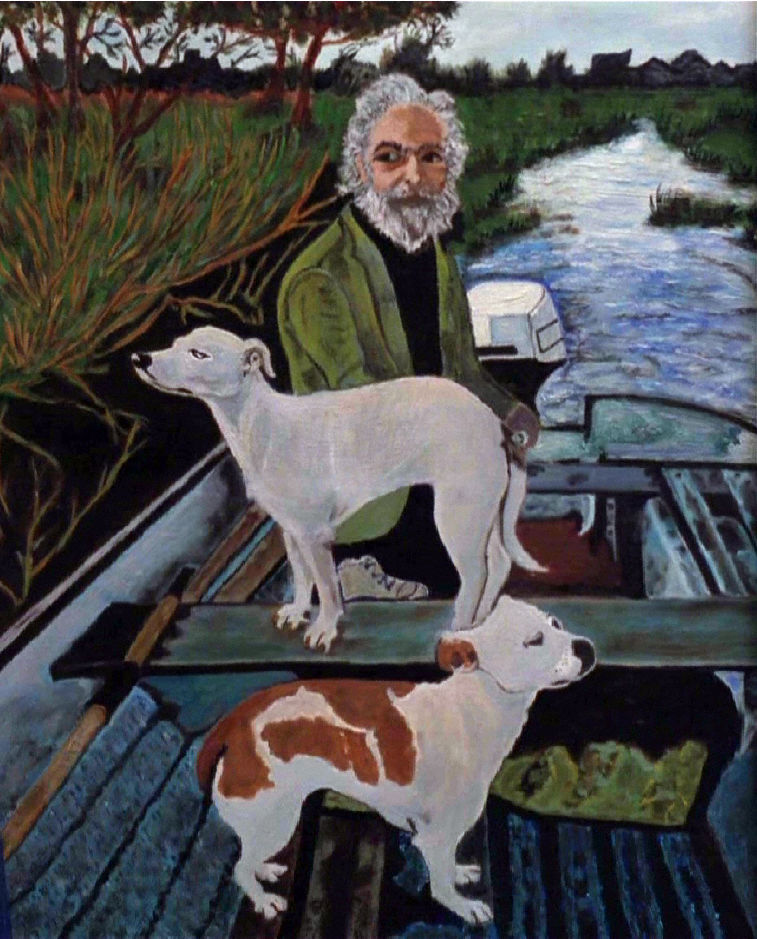

Goodfellas

Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990) also features a highly iconic and memorable painting. After bludgeoning Billy Batts to near death at a bar, Tommy, Henry and Jimmy drive (with Batts in the boot) to Tommy’s mother’s house. There they have a sit down meal and exchange small talk. In conversation with his sweet and elderly mother, it’s amusing and slightly horrifying that every sentence that comes from Tommy’s mouth has a double meaning. ‘Ma, I’ve been workin’ nights’ is particularly memorable. After such pleasantries, Tommy’s mother shows the boys her painting.

MOTHER: Have some more. You hardly touched anything. Did Tommy tell you about my painting? Look at this. (Pulls out an oil painting from alongside the refrigerator.)

JIMMY: It’s beautiful.

TOMMY: I like this one. One dog goes one way and the other goes the other.

MOTHER: One’s going east, the other’s going west. So what?

TOMMY: And this guy’s saying, “Whaddya want from me?” The guy’s got a nice head of white hair. Beautiful. The dog it looks the same.

JIMMY: Looks like somebody we know.

TOMMY: Without the beard! Oh no, it’s him! It’s him. (A thumping noise is heard through the open window from the trunk of the car parked outside.)

Sometimes in a scene, the inclusion of a painting as background décor is enough. In other circumstances like this scene in Goodfellas, it’s the dialogue that makes the painting memorable. The men distort the innocent depiction of a man with his hunting dogs, to something dark and sinister. By comparing the likeness of the painted man to Billy Batts, who is lying close to death in the trunk of their car, the divisions and crossovers between Tommy’s home life and Tommy’s life as a gangster become clearer to us. The painting characterises Tommy’s mother as naive but lovely. She’s a woman who makes dinner for her son and his friends at 3am in the morning, and doesn’t bat an eyelid at Tommy hastily announcing that he’s going to take a large kitchen knife. This is the world of blissful ignorance in which the families of gangsters live in. – that everything is perfect, and everything in normal. I mean, of course it’s normal to have a date night for the wives and date night for the girlfriends every week! The showing of the painting perpetuates this ignorance.

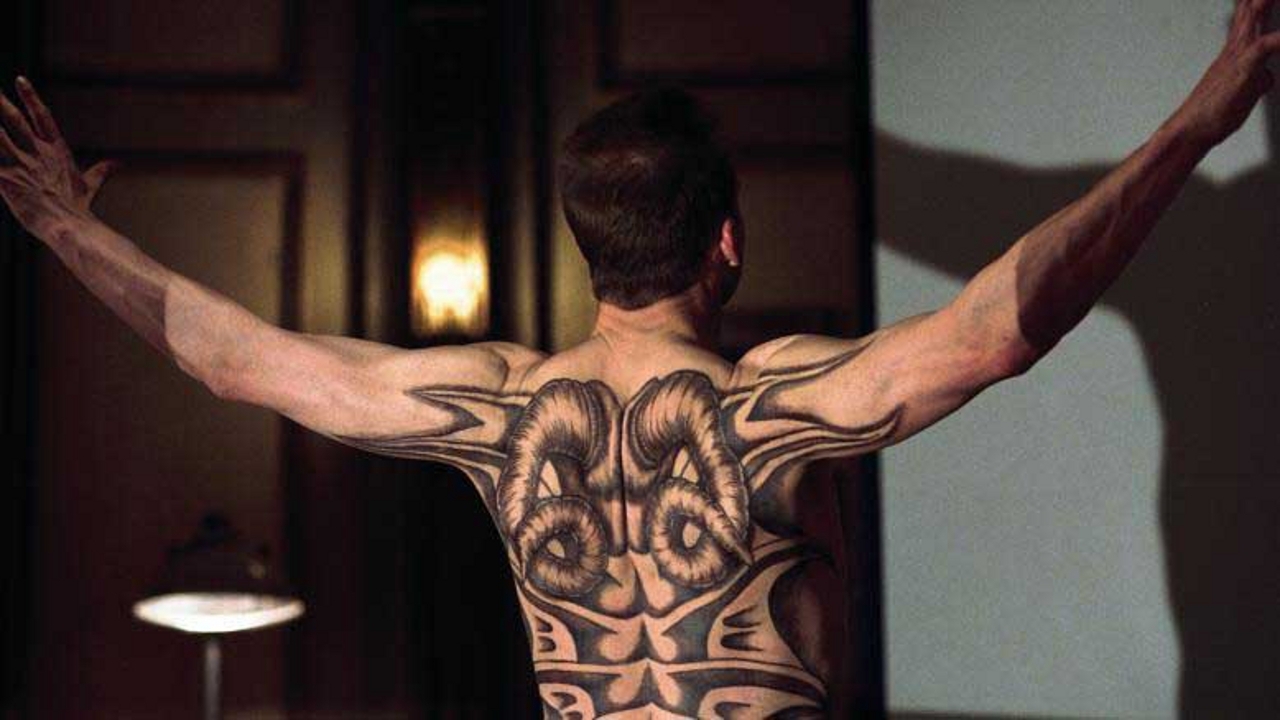

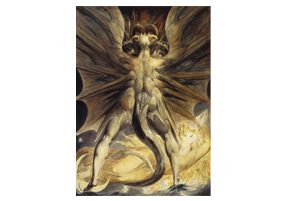

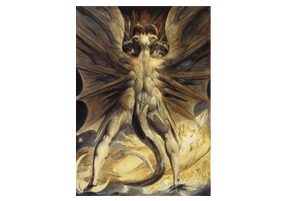

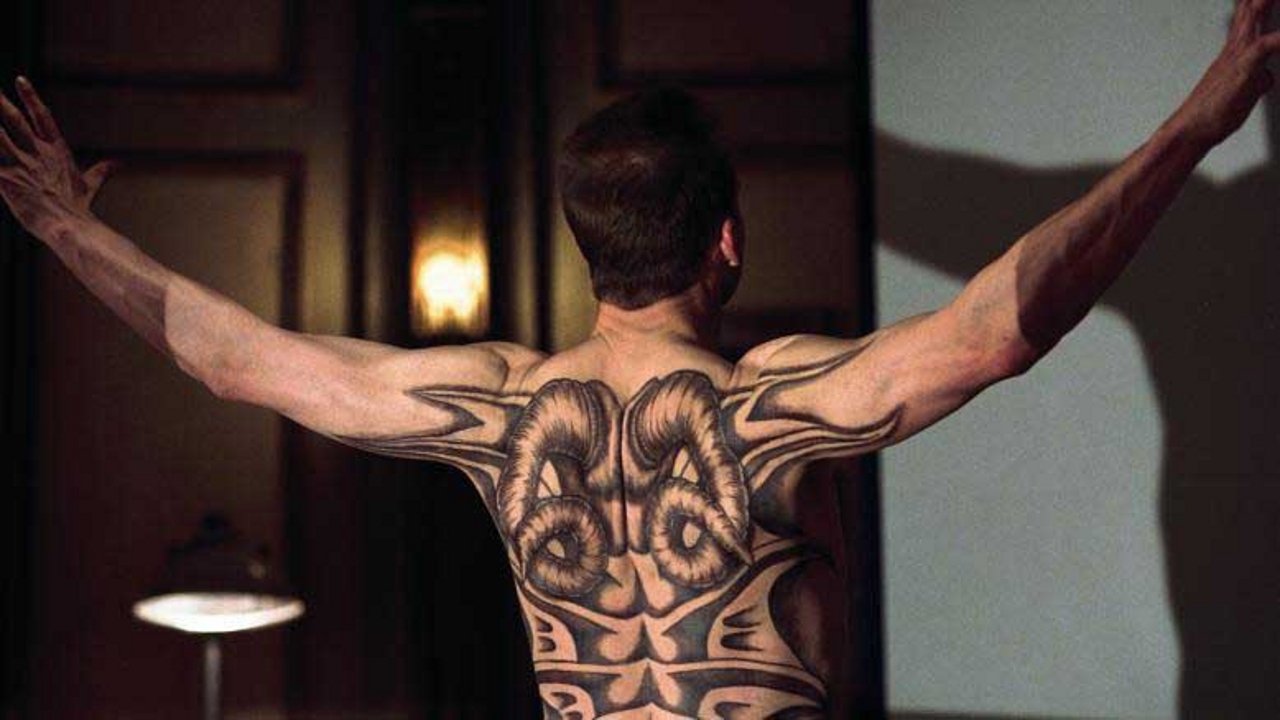

William Blake in Red Dragon

The function of the painting known as The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in Sun by William Blake is explicitly utilised in Thomas Harris’s Hannibal series, as well as several screen adaptations.

Francis Dolarhyde (played by Ralph Fiennes), otherwise known as “The Tooth Fairy”, is the (likely schizophrenic) serial killer and primary antagonist of Red Dragon (2002). He operates by carefully tracking down families, and murdering them by shooting them in their beds. He was nicknamed “The Tooth Fairy” by the tabloids due to the strange bite marks left on his victim’s flesh. Dolarhyde’s upbringing and low sense of worth culminated in part due to a facial disfigurement. He also suffered systematic abuse from his Grandma as a child, and throughout the film is seen talking to her. This could be Dolarhyde reliving the experiences he suffered as a child, or experiencing extreme hallucinations.

The character frequently refers to ‘The Great Red Dragon’, an entity that exists within him, separate from the identity of Francis Dolarhyde. The dragon is a ravenous beast that’s appetite for violence and murder must be quenched if Francis is to fully undergo his transformation to become him. The character goes to such lengths to embody Blake’s Red Dragon that he physically tries to resemble it.

Only when he achieves a sense of peace and acceptance in girlfriend Rena does his interpretation change of who and what The Great Red Dragon is. Whilst the Red Dragon sees Rena as a captive victim much like the Woman Clothed in Sun, Dolarhyde sees her as a companion figure. Afraid of the creature taking her, he travels to the Brooklyn Museum where he eats Blake’s painting, hoping that the darkness within him will leave. I believe the desecration and consumption of the painting is Dolarhyde’s attempts to free himself the Dragon’s hold on him, and let him live out life free from the dominant personality. The other interpretation shared by many is that by ingesting the painting, Dolarhyde can complete his transformation in becoming The Great Red Dragon.

The function of the painting in Red Dragon relies somewhat on our own understanding of Blake’s paintings and their religious connotations.

“The book of Revelation, the final book of the New Testament, contains a series of warnings to Christians to maintain and guard their faith, then relates a series of allegorical episodes that demonstrate the consequences of spiritual defection. The dragon embodies Satan. His mission is to exact revenge on the woman who has given birth to a follower of God who will spread the Christian faith.” says The National Gallery website.

This, however doesn’t stop us from understanding its importance. To Dolarhyde, it is a painting of aspiration – an image of what he strives to become. The painting also acts as a device to highlight Dolarhyde’s Jekyll and Hyde personality, showing us the fight for dominance from the opposing sides of himself.

Paintings in film are all that they are, and more. They can foreshadow a film’s events, they can help a character solve a mystery (the museum scene in Vertigo), they can symbolise a character’s ambition (Red Dragon), their struggles (Skyfall), their sentimentality (The Grand Budapest Hotel), or their ruthlessly yuppy culture (Robert Longo paintings featured in American Psycho). By featuring them, directors and set decorators give us the unique opportunity to interpret and perceive our favourite paintings differently, through the world he/she has created. That’s a wonderful thing to have.

Eleanor Elliott-Rathbone

Eleanor on Twitter

Eleanor on Instagram

The National Gallery have a range of merchandise including these cushions featuring Turner’s, The Fighting Temeraire which played a role in Skyfall. Made with a super soft faux suede, machine washable and come complete with the cushion pad: Buy Here >

The National Gallery have a range of merchandise including these cushions featuring Turner’s, The Fighting Temeraire which played a role in Skyfall. Made with a super soft faux suede, machine washable and come complete with the cushion pad: Buy Here >

Buy an A1 fine art print of William Blake: The Red Dragon, Fine Art Print – the obsession of Dolarhyde in Red Dragon here >

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Instagram

Instagram Pinterest

Pinterest RSS

RSS